Two more years of shortages: no “chips to make chips”

- The global industry association says that securing chips for semiconductor manufacturing equipment is critical at this point.

- Considering that semiconductor fabrication plants (fabs) will take years to build, SEMI doesn’t see the chip shortage easing quickly or soon.

- With a total of 92 fabs in the pipeline by 2024, oversupply is ‘definitely a concern,’ a SEMI expert shared.

The predicted date for when the global chip shortage will come to an end has changed a few times over the last two years. Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the supply of semiconductors was expected to recover by the second half of 2022. Then came the invasion, and some of the world’s most important economies, including China, went into lockdown again – causing further delays in the recovery process.

While hiccups in the recovery process were nothing new, the disruption at the beginning of 2022 came amid facility expansions and the ramping up of production. According to SEMI, a global association of companies involved in the electronics design and manufacturing supply chain, there are 92 fabs in the pipeline.

But that is not the problem.

The issue is that there are insufficient chips available for manufacturing equipment as part of capacity expansions. SEMI President and CEO, Ajit Monacha, described the ongoing issue as “complex,” emphasizing that the recovery will have to start by addressing the toolmakers of these chips. “We are faced with a bigger problem where toolmakers need chips to help grow their capacity. They need chips to make more chips,” he shared during SEMICON Southeast Asia 2022, in Penang, Malaysia.

For context, Penang, dubbed as the “SIlicon Valley of the East,” is home to many semiconductor players from around the world. Multinational corporations (MNCs) including Advanced Micro Devices, Analog Devices, Agilent Technologies (formerly Hewlett Packard), Broadcom, Lumileds, Jabil, Renesas, Western Digital, Intel, Dell, Osram, Infineon and Micron, have all set their presence in that state.

Some of these companies have been around Malaysia since the 1970s. The Malaysian semiconductor market has largely been dominated by labor-intensive outsourced semiconductor assembly and test (OSAT) companies.

Russia-Ukraine Conflict Extends the Chip Shortage by Two Years

From SEMI’s perspective, the unsettled Russia-Ukraine conflict is adding “more fuel to the fire,” said Ajit, mainly because the materials needed from Ukraine, including neon and palladium, among others, cannot be sourced as easily elsewhere. Russia controls as much as 44% of the global palladium supply, while Ukraine produces a significant 70% of the global supply of neon – two necessary raw materials needed for chip making.

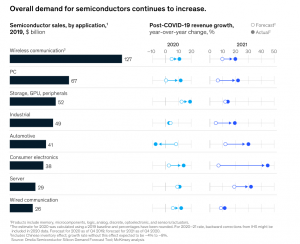

These chips are necessary in almost all other industries, from car manufacturing to mobile phones, consumer electronics and many others. A recent report by McKinsey explained that another problem in the chip shortage is that many semiconductors are transported by air, but transport costs have significantly increased in recent years, while available shipping volume has dropped.

In his presentation at the SEMICON gathering last week, Ajit said that the 92 new fabrication plants being built are expected to be operational worldwide in the next few years, mainly to cater to the surge in demand for semiconductors. But, considering those plants will take years to build, Ajit doesn’t see the chip shortage easing in the short-term future.

Overall demand for semiconductors continues to increase. Source: McKinsey

Reiterating his point, Ajit said that the primary concern for the industry as of now is still the lack of chips necessary for toolmakers to manufacture chip-making machines. “We now need chips to make chips and we have been leading the call for the industry to prioritize toolmakers,” he said. “The fundamental problem of (the) capacity issue is to get tools, and (for) tools, they need chips to make multiple chips,” he added.

To overcome this Catch 22 situation, Ajit said that players within the supply chain would have to come together. “At SEMI, we are trying to bring the entire value chain together, to create awareness, to encourage information sharing where we can be transparent with each other, so the problem can be solved. This will keep people moving forward with what they need,” he explained.

Even semiconductor players themselves don’t see the situation easing anytime soon – or even until 2024. For Ajit, by 2024, with more capacity, the players will finally be able to balance supply against the mounting demand. Till then, we can expect the shortage to remain an issue.

Should oversupply be a concern after chip shortage?

The SEMI data suggests the 92 fabs will come online between 2020-2024, and that theywill comprise a cobination of 200mm and 300mm fabs. For 200mm, 25 fabs and expansions are expected; five in America, three in Europe and Middle East, and 17 in Asia. With 300mm, there are 67 fabs (new and expansions) expected, with seven in the US, eight in Europe and the Middle East, and 52 in Asia.

Considering that the chip industry is a cyclical sector, Sanjay Malhotra, SEMI’s VP of the corporate marketing and market intelligence groups, explained that the current period of consistent shortages suggests there will be a period of oversupply at some point in the future. Speaking to Tech HQ at SEMICON SEA 2022, Sanjay said “an oversupply is inevitable, the smarter companies will switch off (expansion), and balancing will occur.”

SEMI estimated in June last year that the construction of close to 30 new fabs would start by the end of 2022. In September, it predicted global semiconductor equipment investment for front-end fabs, where the silicon wafers are processed, will be nearly US$100 billion next year, after topping US$90 billion in 2022– both of which were records.

This will mark a “rare three consecutive years of growth that began in 2020, bucking the historical cyclical trend of a one- or two-year expansion, followed by a year or two of tepid growth or declines,” SEMI said. Separately, McKinsey also emphasized that there are no short-term solutions for the semiconductor crisis.

“The lead times for chip manufacture average a minimum of four months if capacity is available and no expansion is required; otherwise, it will likely take a minimum of 18 months. Increasing production might seem like the obvious answer, but it takes more than three years to build a new fab and ramp up wafer production. Lead times for manufacturing equipment have also increased over the past two years because Covid-19 complicated supply chains, making expansion even more difficult,” the report added, echoing SEMI’s sentiments.

On top of the unprecedented confidence to expand capacity, governments around the world have committed to spending billions of dollars to expand semiconductor production within their own borders – measures designed to protect against supply chain disruptions like those caused by the pandemic, and to reduce reliance on production in Taiwan.

After closely examining the industry, including these recent supply and demand trends, McKinsey concluded that the semiconductor shortage will likely persist in selected technology nodes for at least the next 3-5 years. “The ongoing shortage is partly a result of longstanding structural factors, such as insufficient capacity, but the recent behavior of automotive companies—over-ordering and increasing stock levels—is also contributing to the problem,” it said.