How do we solve the contact-tracing app privacy problem?

- Relying on access to citizen’s mobile location data, contact-tracing apps are touted as a key tool in fighting the further spread of the coronavirus

- Governments and private organizations around the world are teaming up for these initiatives

- But the use of this data raises privacy issues, and concerns around how that data could be accessed and used in the future

As countries begin to feel their way towards exiting lockdowns, many are pinning their hopes on data and digital technology to manage the COVID-19 outbreak.

Governments all over the world are rushing to enact new measures or invoking emergency powers to facilitate gathering and analyzing data, especially from mobile devices.

Of particular interest is managing the epidemic through contact tracing or tracking down and isolating persons that have come into contact with an infected person. Long a technique of epidemiology, the practice is being transformed – and supercharged – by digital technology.

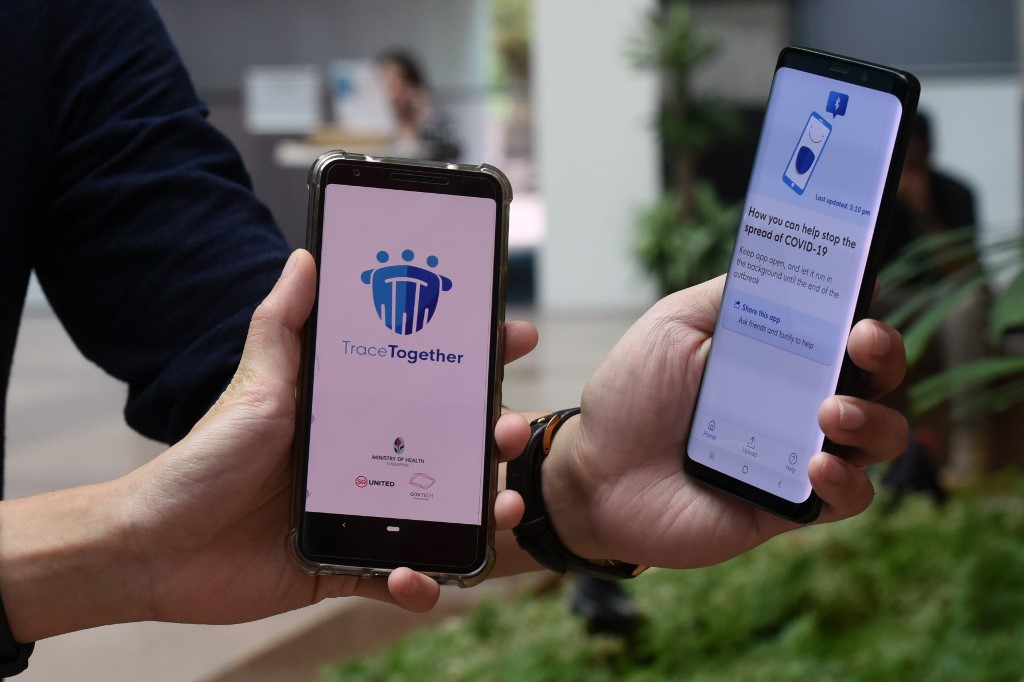

Multiple governments have rolled out mass consumer apps to track individuals, such as the Singapore government-developed app, TraceTogether. European governments are also beginning to roll out their own voluntary tracking apps.

In an unprecedented display of cooperation between otherwise bitter rivals, Apple and Google have announced a joint initiative to develop APIs that enable public health authorities to build apps that perform automated contact tracing, by allowing both iPhones and Android devices to swap anonymous identifiers wirelessly over Bluetooth.

A similar EU-wide effort also uses Bluetooth identifiers to develop a common platform for European apps.

Government Technology Agency (GovTech) staff demonstrate Singapore’s new contact-tracing smarthphone app called TraceTogether, as a preventive measure against the COVID-19 coronavirus in Singapore. Source: AFP

The Great Data Grab

However, building and then asking citizens to download apps takes time, and some governments are looking to go further to conduct contact tracing and manage public health.

Existing data already being gathered by the private sector – usually telecommunications service providers – is proving far more tempting for some governments. In some cases, sharing is not optional.

Israel passed an emergency law to allow the use of mobile data in contact tracing, using it to identify and notify those who must self-isolate. While details are unclear, it seems the intelligence services had collected location data from telecom providers over a period of weeks, then passed it to public health officials.

Perhaps the most aggressive (after China) has been South Korea. As a result of challenges encountered in the 2015 MERS outbreak, South Korea already has a sweeping law in place that requires companies to disclose location data on individuals that are both actually and merely suspected of being infected.

The government has exercised these powers aggressively, scooping up data – from geolocation to credit card transactions – on potentially tens of thousands of its citizens and publicly disclosing information on the movements of confirmed cases.

Pedestrians wearing face masks cross the road in Seoul, South Korea. Source: AFP

Overreach and backlash

While the public health value of more aggressive uses of personal data is clearly apparent, so are the risks. Once provided with extraordinary access, governments don’t often want to part with new tools and authorities, creating the possibility for a new ‘normal’.

Over time, there is a risk that law enforcement or surveillance authorities will seek to tap into such fonts of information, as has been the steady trend in counterterrorism surveillance for nearly two decades.

Some are already ringing the alarm bell. The European Data Protection Board recently warned that personal data processing for public health purposes must still comply with fundamental principles of the European framework such as minimization and privacy by design, as well as clear legal bases, including consent or specific national legislation.

Civil society groups in several countries are already flagging concerns, such as in Israel for example, where the government won the authority without formal endorsement of the legislature, or in the UK, where advocates have warned the National Health Service against such practices.

The public has started to take notice as well. In France, though technical details of the government’s forthcoming “Stop Covid” app are still taking shape, public concerns about enhanced surveillance are already high. A recent survey found that 53 percent of the public would oppose using such an app over concerns of privacy and confidentiality.

The danger is not just of government abuse, but also of private abuse that careless government disclosures enable.

In South Korea, after the government began releasing information about the activities of affected individuals, online groups began to piece together information and speculate which of their neighbors had been infected, as well as gossip about what private information they could infer – such as alleged marital infidelity.

As a result, some surveys show that individuals in Korea are almost as afraid of public shaming as they are of contracting the virus. As a result, South Korea recently recalibrated its privacy guidelines after causing harm with over-disclosure.

Finding the balance

Going forward, it is almost certain that more states will follow the path South Korea did in response to MERS to facilitate public health authorities’ access to data.

However, governments should also heed Korea’s more recent example and recognize that there are risks from overreach, too. To safeguard public trust, governments should think and communicate clearly what they want to accomplish and the tools they need to do it.

And when they do need personal data, they must have clear prohibitions on sharing with other public authorities unrelated to public health, retention limits, guardrails around public disclosure, and better thought-through anonymization protocols. Companies will also need to focus on transparency and honesty to help build trust.

Well-constructed apps may be part of the answer. Despite the bad reputation the tech giants have developed for their privacy practices, the private sector is currently enabling some of the most privacy-protective solutions – such as the Apple/Google initiative – and should be encouraged to continue doing so.

In contrast to dragnet approaches based on potentially invasive uses of geolocation data, focusing narrowly on interpersonal contact – not geolocation or other forms of personal data – may balance actual usefulness versus risks of overreach best.

This article was contributed by Logan Finucan, Senior Manager of Data & Trust at Access Partnership.