Inside the transition of power at IBM

The year “2020” has practically become synonymous with the US Presidential election, but it actually opened up with the transition of significant, corporate power.

IBM CEO Ginni Rometty stepped down. The transferring of power is always political, even at a 108-year-old computer company, and Rometty endured the costs and criticisms of strategic, technological shifts.

IBM’s new CEO Arvind Krishna is tasked with realizing some of her investments, correcting missteps, and changing perceptions. Rometty will retain her position as chairman of the board until the end of this year, then retire after a 40-year career at IBM.

Krishna, formerly SVP of Cloud and Cognitive Software, appreciates the gains that could be realized through AI but he also appreciates the work required.

Arvind Krishna, IBM’s new CEO. Source: AFP

He has observed that some companies tire out just by collecting and cleansing the prerequisite data. When asked how many of IBM’s AI-related projects and partnerships were halted, Krishna noted that in the world of IT, roughly half of all projects are late, over budget, or halted, and AI is no exception.

Krishna will be supported by Jim Whitehurst in the role of President, who also has an appreciation for the bigger picture. As a strong supporter of STEM education and the open-source movement, Whitehurst understands how to balance commercial interests with community needs. He was President and CEO of Red Hat when it was acquired by IBM for US$34 billion, and before that, he was COO at Delta Airlines.

After the acquisition, Whitehurst made it clear that Red Hat would remain a distinct unit in IBM and continue to honor its role in the enterprise, open-source community, with even greater reach and resources. Together, they could serve the global market and overwhelming shift to multicloud, with Linux acting as an innovation engine.

But Krishna and Whitehurst are taking over during highly charged times. Online business and technology forums are filled with invective directed at Rometty. One thread, regarding IBM layoffs, suggested, “Replace Ginni with new blood or even with a modified WATSON system and IBM will start to grow, quickly.”

Rometty broke the glass ceiling as IBM’s first female CEO. The tech industry still struggles with inclusion, despite evidence that gender-diverse and ethnically-diverse companies financially outperform their national industry medians. When Rometty first got the job, her predecessor, Samuel J. Palmisano, made sure to note that her advancement was wholly based on merit.

“It’s got zero to do with progressive social policies,” he told the New York Times in 2011. It did have a lot to do with Rometty leading a tactical shift into services. She realized that enterprise clients were more interested in bundles of technology that could be presented to them as dynamic, relevant, integrated business solutions. Gone were the days of standalone hardware and software products that required technical interpretation and looked like ticking timebombs of obsolescence.

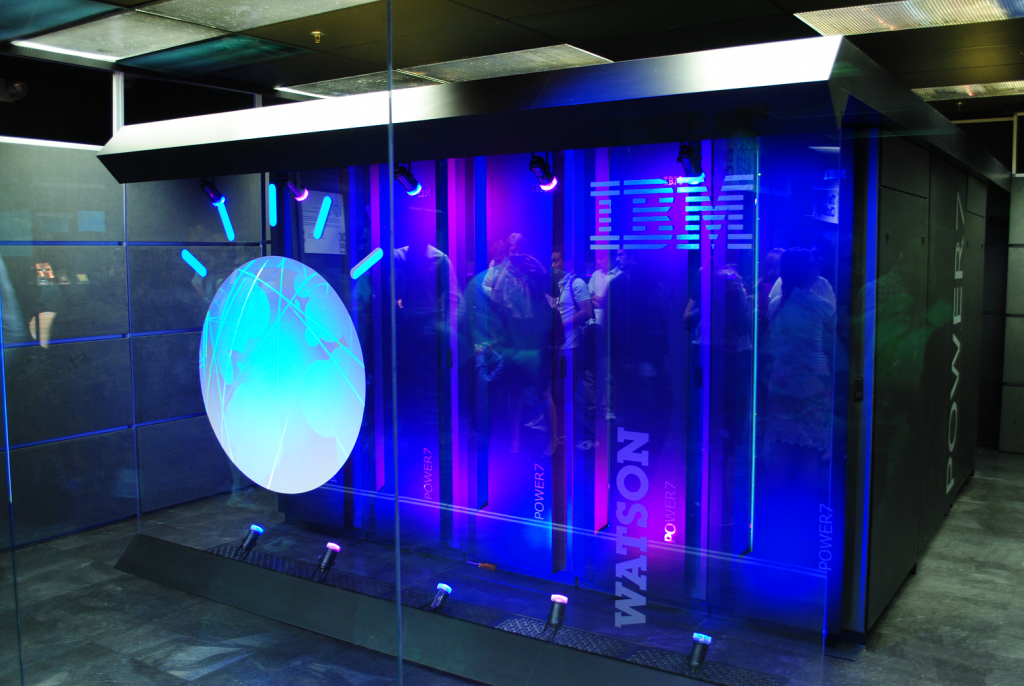

During Rometty’s time as CEO, she continued that modernization and transformation by capitalizing on IBM Watson, which will almost certainly be noted in the history books as a key point in AI’s evolution and commercial applications.

IBM Watson. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Rometty’s critics point out that she received exceptionally high pay while overseeing a company with 22 consecutive quarters of falling revenue. But massive, old companies often have layers of middle management, scattered divisions, and legacy products and business models, which slow them down, and some of those quarters could have been the cost of realigning the company with technology’s newest, high-growth categories in a meaningful way.

A New York Times DealBook memo appraised her performance bluntly. “She became one of Corporate America’s top women leaders — but couldn’t finish turning around her own company’s fortunes,” it stated.

“She struggled to make IBM more relevant,” the piece added, before noting that shares in IBM fell 25 percent during her tenure, in contrast to Microsoft shares, which jumped 500 percent. An LA Times piece claimed that “Rometty became an exemplar of the dysfunction in executive compensation in US industry” and opined that a board of similarly predisposed current or former CEOs enabled these rewards despite Rometty’s “lousy record.”

IBM’s press release noted that Rometty successfully acquired 65 companies and reinvented more than 50 percent of IBM’s portfolio, building a US$21 billion hybrid cloud business and establishing IBM’s leadership in AI, quantum computing, and blockchain. A CNBC headline declared simply: “IBM was the worst-performing large-cap tech stock during Rometty’s tenure.”

Some analysts said she should have done more to cash in on social and mobile, essentially framing every area of tech profitability as a relevant but fumbled play for IBM. IBM’s failure to keep pace with Amazon and Microsoft in the competitive cloud market is fair game, but IBM in social? Really? That just sounds like another Google Plus.

YOU MIGHT LIKE

IBM acquires Red Hat to help pave the way cloudwards

Other observers might see the “glass cliff” in Rometty’s story, or in the story of Mary Barra, who was also an internal promotion to CEO at an old, corporate giant. Barra took over at GM, during a time of 84 safety recalls involving over 30 million cars. Were these women being set up to fail?

An academic paper from 2005 examined the performance of FTSE 100 companies before and after the appointment of a male or female board member. During a period of overall stock‐market decline, the companies that appointed women to their boards were more likely to have experienced consistently bad performance in the preceding five months than those who appointed men.

That could be interpreted to mean that the tumultuous times were somehow able to shake out ingrained biases, or it could be interpreted to mean that women are being installed as possible scapegoats, an idea explored in the book “The New Soft War on Women: How the Myth of Female Ascendance Is Hurting Women, Men — and Our Economy.”

While delivering a keynote speech at the Grace Hopper Celebration for Women in Computing, Rometty once revealed an insight into her past, and herself.

“When my father left us, my mother went back to school immediately,” Rometty said. “She went to school in the day while we were at school and she worked at night. She worked very hard to never let someone define her as a victim or a failure.”

Rometty concluded, “You never let someone define who you are. Only you define who you are.”