Consumer tech will change the world — If we let it

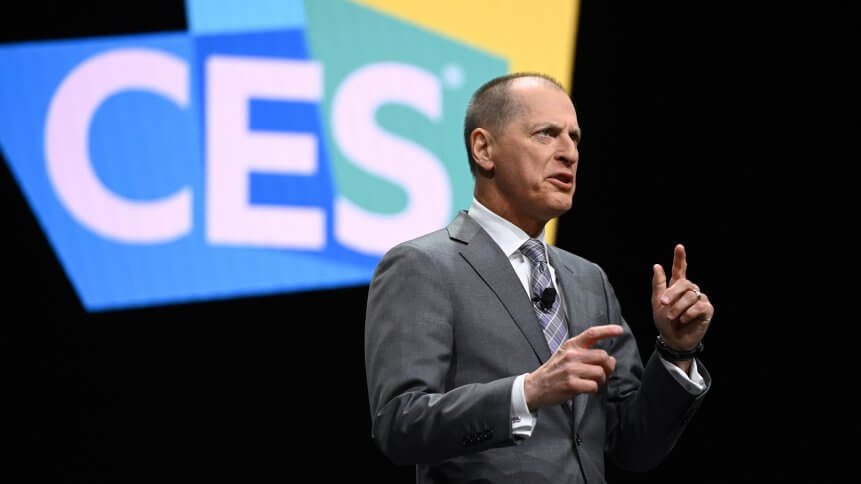

In late January, I conducted a wide-ranging interview with Gary Shapiro, President of the Consumer Technology Association, and he kindly shared his thoughts on innovation, social change, and risk.

A lot of that business risk has strong political undercurrents. Shapiro says that “tariffs are taxes” and the US-China trade agreement is “a mixed bag.”

Reflecting on my conversation, three important lessons jumped out — 1) Risk is essential for meaningful consumer tech. 2) Consumers want sustainability and companies are responding. 3) We need to be reasonable. Perfect is the enemy of good.

Technology now touches upon nearly every aspect of daily living. This naturally makes it a catalyst for social change and a topic of interest for diverse stakeholders. The next wave of technologies will be even more capable and transformative. How can policymakers support the entrepreneurs who are trying to do the right thing and absorbing a lot of the associated risk? In many instances, politicians ought to engage with and listen to the tech sector, instead of broadly condemning it and ignoring nuance.

Shapiro’s standards and trade organization represents over 2,000 companies in the U.S. consumer technology industry, a massive, US$422 billion space that supports more than 18 million jobs. 80 percent of the CTA’s members are considered to be small businesses and startups. The CTA currently produces the annual Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas.

Why risk is essential for meaningful consumer tech —

“Amid the lights and shine of CES each year, it’s easy to forget one simple truth: No one got here by playing it safe,” Shapiro recently wrote in a LinkedIn post.

There’s an intimate relationship between tech-enabled disruption and risk. One CES exhibitor, Hydraloop, was motivated by its vision for a more sustainable future. The company hopes that in 20 years’ time, all new buildings will be equipped with their own greywater recycling systems.

“The biggest risk that we’ve taken is that we are investing our own money that we’ve earned […] so this is our pension,” said co-founder, Sabine Stuiver.

“And we’re investing it in this. We could have not done that. We could have lived a beautiful life and never had to work again. But this is what we believe is what has to be done. We are on a mission.”

Consumers want sustainability; companies are responding

When I asked Gary Shapiro about sustainability in the consumer tech space, he said that this product category is consuming less and less energy in the average home. He explained, “Despite the fact that we’ve had an increasing number of products in the home, the actual usage as a percentage of energy in the US continues to go down every year.

“Probably the best example of that is a TV set which 15 or 20 years ago was a big fat cathode ray tube, weighed a few hundred pounds, sold for a lot more money, and today, you get this slim little thing that barely uses the electricity of a lightbulb. And that’s your TV set today.”

The Energy Star certification program has also helped to guide consumer choices. In 2017, it helped consumers save 170 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity and avoid US$18 billion in energy costs.

Shapiro continued, “The good thing about our industry is that every incentive is on the manufacturers to figure out ways not to generate heat, because heat uses a lot of electricity and causes breakdown in products. So whether it’s a laptop or a TV set or a phone, the effort is how can you get it down to smaller and smaller multi-chip module chips, which have fewer mechanical parts than any device and use less energy.”

But that’s just one aspect. Shapiro noted that companies need to be cognizant of various chemicals that are used. They need to comply with laws and ideally do more than what is required. They need to think about recycling and reuse.

As for its own events, the CTA has detailed what they’re doing to make CES green. At CES 2019, this included the recycling of over 1,400 tons of materials.

“You know, the average person that comes to our show has 33 meetings,” Shapiro told me. Consolidating meetings into one event, he argues, is vastly preferable to taking separate trips. Although teleconferencing and phone calls can handle some of that, Shapiro said there’s still a need for face-to-face meetings, conferences, exhibitions, “and all sorts of things where you’re establishing relationships, seeing if you trust someone, using your five senses, and you also have the benefit of serendipity that way.”

YOU MIGHT LIKE

Inside the transition of power at IBM

Why perfect is the enemy of good

In February, the House Energy and Commerce Committee held a hearing on autonomous vehicles, through the Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce. Shapiro testified that AVs could lead to an enormous reduction in roadside fatalities and he argued that perfectionism may be an unreachable and even dangerous goal, if it interferes with progress and near-term deployment.

He cited a RAND report, which evaluated 500 plausible futures and concluded that it makes sense to introduce autonomous vehicles on the roadways provided they are 10 percent better than a human driver. This less-than-perfect standard actually saves more lives in the long run; waiting for the cars to be 75 or 90 percent better than human drivers is the more dangerous scenario.

The perfectionist standard also restricts personal freedom and fulfillment. A study from the Ruderman Family Foundation estimates that the realization of AVs in the United States could open two million employment opportunities for people with disabilities.

Extolling the benefits of self-driving vehicles, Shapiro testified, “They don’t get distracted, they don’t get tired, they don’t drink too much. They save lives, prevent injuries, and empower seniors and people with disabilities.”

In some respects, a counterintuitive argument is being presented to society: Accept risk. It’s in your interests. But the business community is already accustomed to this line of thinking, especially in Silicon Valley.

“People love to focus on things that aren’t yet working,” Amazon founder, CEO, and President Jeff Bezos once said. “And that’s good, it’s human nature, and that kind of divine discontent can be very helpful.”

But not always.

Bezos continued, “It’s incredibly hard to get people to take bold bets. And you need to encourage that. And if you’re going to take bold bets, they’re going to be experiments. And if they’re experiments, you don’t know ahead of time whether they’re going to work. Experiments are, by their very nature, prone to failure. But big successes, a few big successes, compensate for dozens and dozens of things that didn’t work. So, you know, bold bets — AWS, Kindle, Amazon Prime, our third-party seller business — all of those things are examples of bold bets that did work and they pay for a lot of experiments. I’ve made billions of dollars of failures at Amazon dot com.”

Bezos conceded that these failures aren’t very fun, and even rattling them off feels like a root canal without anaesthesia, but he also said that these things don’t really matter. What really matters is that companies embrace their failures and continue to experiment. Otherwise, desperation and obsolescence are right around the corner.

This is good advice for individual technology companies but perhaps it’s also relevant to the tech industry and the planet as a whole. Earth is facing a climate crisis. Policy is interfering with global cooperation and trade. We need to innovate and we need to take managed risks, before desperation and obsolescence become a humanity-wide problem.